Across mammals, females experiencing adverse conditions during gestation can transfer the stress information to the embryo/fetus via the placenta (circulating glucocorticoids), and induce epigenetic programming of neurological, immune, metabolic, and reproductive functions of the offspring. However, the nature and persistence of such effects (adaptive vs detrimental; short-term vs long-term) is still under debate.

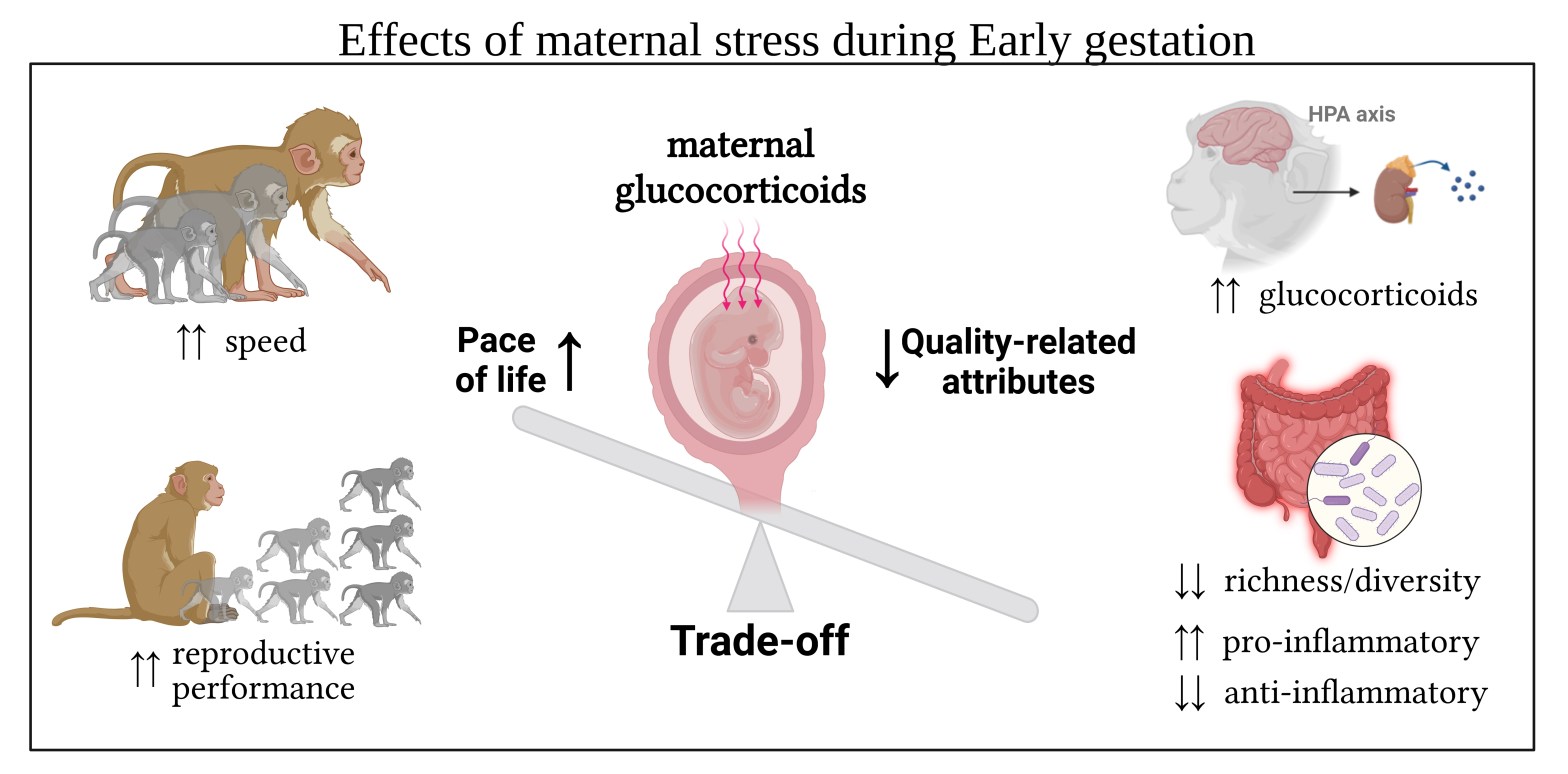

My Ph.D. thesis is a four-studies contribution to the ongoing debate on the nature of responses to prenatal maternal stress, and relying on strategic trade-offs between offspring body growth and their quality-related attributes. I combined long-term data on maternal glucocorticoid levels (GCs) with (i) GCs of infant, juvenile and adult offspring, (ii) information on their gut microbiome community, (iii) their body growth and (iv) their reproductive performance as a proxy for their pace of life.

In the first study, I observed that maternal GC levels during gestation were associated with increased activity of the offspring’s HPA axis (higher GCs). Importantly, such hyperactivity was equally observed in adults, juveniles, and infants of different cohorts, but only if maternal GCs increased during early gestation. Moreover, prenatally challenged females showed accelerated reproduction as clues of the higher pace of life associated with maternal stress during gestation.

In the second study, I investigated the effect of prenatal maternal stress on offspring gut microbial diversity and composition. Consistently, I found that higher maternal GC levels during early gestation were associated with a reduced bacterial richness, increased relative abundance of several pro-inflammatory organisms, and a reduced abundance of many anti-inflammatory ones, with a generally lower energy-harvesting capability of the bacterial community. Interestingly, the results also suggest a better energy-harvesting capability of the microbial communities belonging to offspring with elevated GCs, and an overall higher energy expenditure in prenatally stressed offspring.

In the third and fourth studies, I first tested different methodological approaches to investigate body growth in a non-invasive way, and then I applied the validated method to test the effect of prenatal maternal stress on body growth. Again, maternal GCs during early gestation were associated with accelerated growth.

Overall, my work shows evidence of long-term detrimental effects of a not-traumatic and naturally driven increase of prenatal maternal stress combined with growth acceleration: prenatally challenged offspring accelerates their life-history pace by increasing growth and speeding up reproduction at the cost of a higher allostatic load and “wear and tear” of physiological systems which can negatively impact morbidity and reduce lifespan.

The gut microbiome plays a crucial role in maintaining overall physiological and psychological health, and immune function. Dysbiotic microbial states contribute to the development of diabetes, heart disease, some types of cancer, autoimmune disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis, but also neurological and psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, autism, and Parkinson’s disease. My work provides a developmental perspective on adult health. Its core lies in the epigenetic effects of maternal stress on the gut microbial community and the results are impressive: there is a measurable gut microbial signature of maternal stress that not only persists into adulthood but worsens with age.

Maternal stress induces long-term dysbiotic states which intensify in older subjects benefitting less from the health-promoting and anti-inflammatory organisms, and paying higher immune-related costs associated with the increase of the pro-inflammatory ones. Therefore, this study affects mostly the scientific community of developmental biologists, veterinarians, medical doctors, and potentially also psychologists. By confirming that health and fitness differences begin in utero, my work underlines the role of epigenetic factors such as maternal stress in shaping the adult’s physiological and psychological health states, and provides a deeper understanding of the developmental origin of health and disease.